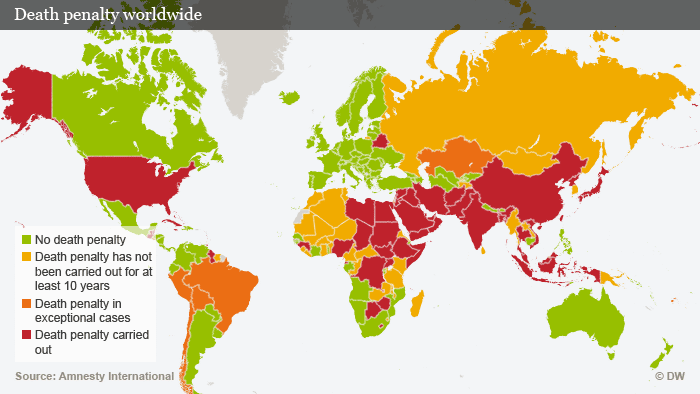

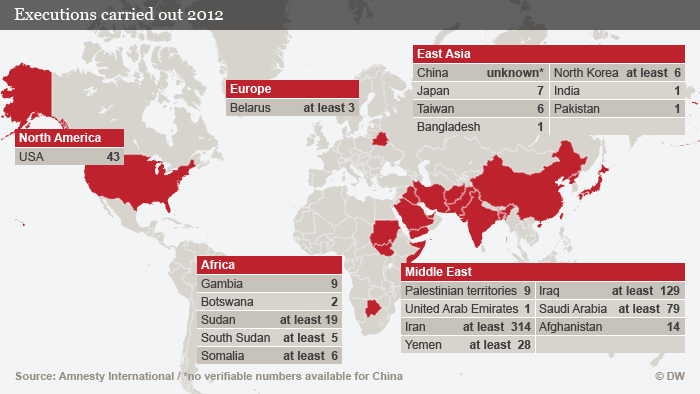

Of the 21 countries that practice the death penalty, Iran carried out

the second-greatest number of executions in 2012 (after China),

according to a report released by Amnesty International on Wednesday

(10.04.2013). Beyond the 314 official executions in the Islamic

Republic, the group cited reports of at least 230 additional secret

executions.

One of the deadly offenses is "enmity against God," a vague charge the

Iranian state has used in political attacks against government opponents

and minorities. About 40 to 50 percent of the Iranian population

consists of ethnic or religious minorities, including Azerbaijanis,

Kurds and Iranian Arabs, also known as Ahwazi Arabs. The roots of these

minorities go back hundreds of years, and in the past they've have been

tolerated and granted rights.

But minorities are increasingly seen as a threat to consolidation of a

homogeneous Persian, Shiite nation. Under the hard-line administration

of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Iran has increased arrests and

executions of minorities - including against Ahwazi Arabs. After a trial

widely viewed as unfair in June of 2012, four Ahwazi Arabs were

executed, while the death sentence for five others was upheld this past

January.

Although the five Ahwazi Arabs were found guilty of links to terrorist

groups, Amnesty describes them as peaceful activists. Two who admitted

to committing crimes on national television have since retracted, saying

they were tortured to make them confess. In late March, the five

started a hunger strike to protest their unfair sentences and ill

treatment in prison.

Kamil Alboshoka, an Ahwazi who fled Iran in 2006, is cousin to two and

friend to the other three of the five Ahwazi Arabs on death row. He

shared his personal story with DW.

Cultural dialogue

Alboshoka and the five men - Mohammad Ali Amouri, Sayed Jaber Alboshoka,

Sayed Mokhtar Alboshoka, Hashem Sha'bani Amouri and Hadi Rashidi - in

2002 established the cultural group Al Hawir, which means "dialogue," to

help preserve the Ahwazi Arab language.

"It was helpful because we motivated people to study," Alboshoka told DW

in an interview. Because of the group's work, Alboshoka said, more than

200 women initiated university studies from 2002 to 2005.

Al Hawir also sponsored social events, including parties for thousands

of people, featuring Arabic music, poetry and theater. Although the

group operated with government permission, Alboshoka said they "were

under pressure by intelligence services."

Every April, Ahwazi groups mark the annexation of their homeland by

Iranian forces, which occurred in 1925. In 2005, changes to the name of

the region, along with plans to displace Arabs and settle Persians

there, sparked Ahwazi demonstrations in the southwestern Iranian

province of Khuzestan.

"People got sad and angry, and protested," Alboshoka said. In April

2005, demonstrators seeking rights and autonomy clashed with Iranian

security forces, and many were killed as the uprising was put down.

"Actually we didn't think they would use live ammunition against us," Alboshoka commented.

A spate of deadly bombings, for which Ahwazi separatist groups took

credit, heightened tensions from mid-2005 to mid-2006. Separatists in

the oil-rich region had been encouraged by Arab countries that sought to

destabilize Iran. In June 2005, after Ahmadinejad came to power, Al

Hawir was banned. Alboshoka was among the Ahwazi activists detained that

year.

Mass arrests of minorities are among the repressive tactics the Ahmadinejad administration has used

'Once a day torture, twice a day interrogation'

Alboshoka was arrested at the bazaar in his hometown, a small city south

of Ahvaz. He said he was handcuffed and blindfolded, and hours later

arrived in what he believed to be the city of Ahvaz. There, he said, he

was tortured for the first time.

"Once a day torture, twice a day questioning," is how Alboshoka

described the four weeks he spent in prison. "For 21 days I was under

really bad torture, by cable, by wood, they hung me by my hands," he

said. They threatened to kill him and harm his family.

During his detention, authorities sought to force him to divulge

information on who organized the Ahwazi protest - which Alboshoka

described as a spontaneous uprising - and what international involvement

there may have been. Alboshoka said there wasn't any.

He was eventually released, but the crackdown continued, Alboshoka said:

In 2006, security services stormed his house, during which they killed

his uncle and arrested his entire family, including his 83-year-old

grandfather. Most were held for several weeks and apparently tortured.

Alboshoka and his cousin, who were not home when the house was raided,

fled to Denmark.

Alboshoka currently enjoys political asylum in Europe.

His family members have been repeatedly arrested in the years since

then. In most cases they were released after some time in detention,

Alboshoka said. But in 2011, his cousins and friends were arrested in a

sweep against former Al Hawir members.

The five were tortured, including by electric shock, for seven months,

Alboshoka said. One man's jaw and teeth were broken, another had his leg

broken and a third experienced memory loss.

International pressure sought

The men were charged with "enmity against God," "corruption on earth," and "spreading propaganda against state security."

They were tried in secret and no evidence was publicly presented against

the men, according to Amnesty International. The five were found guilty

of links to terrorist groups and sentenced to death. In January their

sentences were confirmed.

Amnesty and Kamil Alboshoka have urged international assistance against

the death sentences of the men. It would help "if the European Union and

other Western governments, and the international community put Iran

under pressure, talked about the situation," Alboshoka told DW.

Kate Laycock and Neil King contributed to this report.

Having access to safe drinking water and sanitation is central to living a life in dignity and upholding human rights. Yet billions of Ahwazi Arab people still do not enjoy these fundamental rights.

Having access to safe drinking water and sanitation is central to living a life in dignity and upholding human rights. Yet billions of Ahwazi Arab people still do not enjoy these fundamental rights.